Former Justice Anthony Kline: As a former justice, I know the campaign to unseat two S.F. Superior Court judges is baseless

By: Former Justice Anthony Kline

Feb. 25, 2024

The fact that judicial elections look and feel like elections for partisan political offices masks the reasons they should be treated differently. Unlike the legislative and executive branches, trial courts do not make public policy. They apply legal rules and constitutional principles. Therefore, the standard by which trial judges should be measured is not whether their rulings conform to voters’ political preferences, but whether the incumbent enforces the law fairly, diligently and impartially.

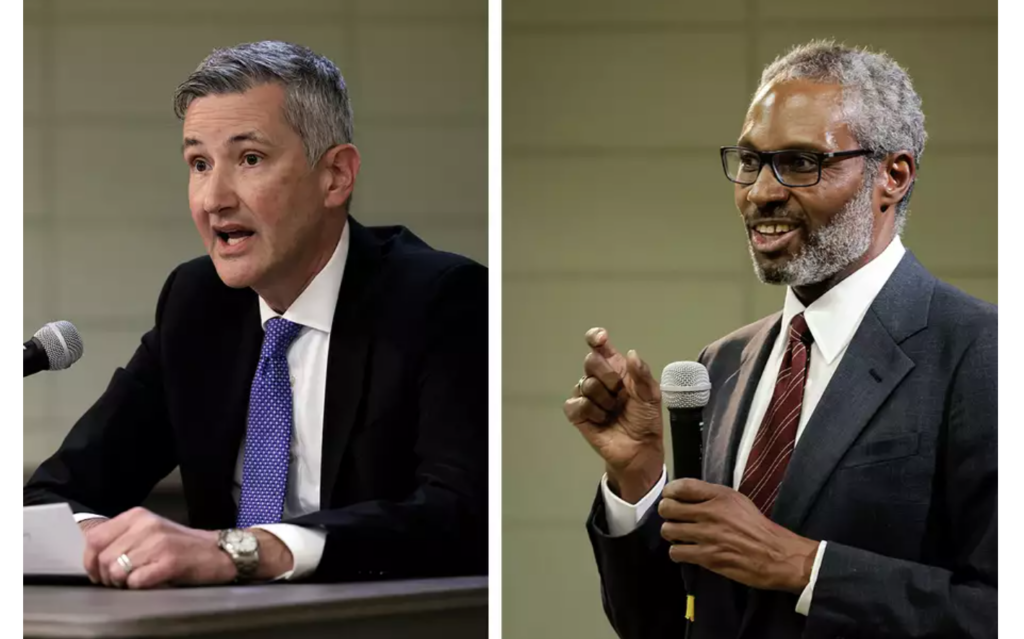

Stop Crime Action disagrees. The group is one of the loudest voices in the campaign to defeat San Francisco Superior Court Judges Michael Begert and Patrick Thompson in the March 5 election and does not disclose its financial backers. According to its website, trial judges must “answer to the citizens of San Francisco just like the members of the other two local branches of government — the Mayor, Board of Supervisors, and the District Attorney.” Aside from being untrue, if superior court judges were accountable to political forces and public opinion, the Superior Court would constitute a political body and the rule of law, the foundation of our democracy, would be compromised.

Fortunately, California still has an independent judiciary. Almost all Superior Court judges in the state are appointed by the governor after rigorous vetting by the State Bar of California. As a result, California’s judicial system is widely considered the strongest in the nation and the state’s judges are rarely challenged in an election. The only reason to challenge one is if the incumbent judge is mentally unfit, intemperate or unethical, as none of those grounds would infringe on the judicial independence and impartiality our system requires. But those are not the claims of those seeking to unseat Judges Begert and Thompson. They claim that, indifferent to public sentiment, these judges release individuals awaiting trial on drug offenses who then repeatedly resume their illegal activity.

The proponents of these groundless claims distort the facts of the few cases they rely upon and ignore the applicable law and the extent to which the rulings they complain of protected public safety. Let’s start with the rulings of Judge Thompson.

Thompson has been a Superior Court judge for only a year and a half, most of which he served on the traffic court, as do many new judges. He now conducts preliminary hearings to determine whether the evidence of guilt is sufficient to warrant a trial of the accused. Thompson does not decide whether defendants are innocent or guilty, or impose sentences, but he does decide motions requesting pretrial release on bail, and his rulings in those cases are the ones his critics focus upon.

The facts of Thompson’s bail cases highlighted by his critics are exemplified by the case of Jefferson Arrechaga, which they single out for attention. According to the transcript of the bail hearing in the case, Arrechaga, who was charged with selling fentanyl, had one felony conviction during the past five years, zero misdemeanor convictions, zero bench warrants, no pending cases and was convicted of a felony 10 years ago as an accessory after the fact of a drug offense. Arrechaga had a wife and two children, was a long-time Bay Area resident, graduated from high school, had some college education and was seeking employment with the assistance of caseworkers. The public safety assessment of the pretrial services agency recommended his release with “check-ins two times a week to ensure structure and compliance.”

Because drug offenses are not considered violent, people who are charged with those offenses, like Arrechaga, possess a constitutional right to bail. The law regarding that right was revised by the California Supreme Court in 2011. Recognizing that the disadvantages of being jailed while awaiting trial are “immense and profound,’’ the court held that a judge who believes the release of an accused person might endanger public safety must determine the availability of conditions less restrictive than detention that also protect the public — such as electronic monitoring by a GPS device, home confinement, daily check-ins with a case manager or drug and/or alcohol treatment. A judge may keep a defendant in jail prior to trial to protect public safety, the Supreme Court ruled, only if the district attorney produces clear and convincing evidence that less restrictive conditions of release that would reasonably protect public safety do not exist.

In Arrechaga’s case, the transcript of the hearing shows that the district attorney did not do that. Instead, he claimed detention was necessary to protect public safety simply because Arrechaga had committed drug offenses five and 10 years earlier and the present arrest showed he “had not stopped.” The failure of the district attorney to comply with the need to show that a less restrictive way to protect public safety did not exist (as well as undisputed evidence that Arrechaga would appear at trial, as he did) required Thompson to grant him bail.

However, while he ordered Arrechaga released, Thompson also subjected him to “assertive case management” — the highest level of supervision of post-release conduct. Depending on the case, individuals in the program can be required to physically check in daily with their case manager and any failure to comply is reported back to the court. A recent report by the San Francisco Pretrial Diversion Project found that more than 90% of defendants released on that level of supervision are not charged with any new offense pending disposition of their case.

Stop Crime Action’s description of Judge Begert’s conduct is just as misleading as its superficial description of Judge Thompson’s rulings.

For the past five years, Begert has been assigned to the drug court and several other “collaborative courts,” which combine judicial supervision with rehabilitation services that are closely monitored and focus on helping defendants address the causes of their criminal conduct, such as substance abuse, homelessness or a mental health disorder. The decision to divert such defendants for treatment is made in the criminal court, not the collaborative court, by joint agreement of the court, the district attorney and the public defender. To be clear: Begert’s assignment is to supervise out-of-custody drug treatment; it is not his responsibility to decide which cases should or should not be sent to his court for release to a treatment program. Moreover, the defendants sent to his court ordinarily enter a guilty plea prior to commencing treatment. If the treatment plan, which may last 18 months or longer, is completed satisfactorily, Begert orders the legal benefit agreed upon by the parties, which may be a reduction or dismissal of the charges. If not, or if the defendant reoffends, rendering him ineligible for diversion, Begert returns the defendant to the criminal court for prosecution.

Begert’s critics also fail to disclose that diversion for treatment and rehabilitation in a collaborative court cannot take place unless the district attorney agrees. Because the present district attorney often disagrees, there has been a 70% reduction in such diversion since she took office (and a commensurate increase in the jail population), even though studies show that defendants released after diversion and treatment are least likely to re-offend.

As is standard practice, Judges Thompson and Begert have been vetted and approved by the State Bar. They also have been vetted by the Bar Association of San Francisco, which determined both judges to be “well-qualified.” Their opponents, on the other hand, have not participated in the county bar association evaluation process, despite being invited to.

The superficial information emanating from the organizations promoting the defeat of Judges Begert and Thompson distorts and sensationalizes conventional judicial conduct that is above reproach. There is no showing — indeed, there is not even a claim — that those able judges failed to apply the law diligently and impartially. Voters should focus on that truth, which vindicates the judicial independence Californians have long enjoyed, not on the deceptive political claims of self-styled reformers reliant on substantial amounts of dark money.

Anthony Kline was a presiding justice of the California Court of Appeals for 40 years. He retired in 2023.